He had told me, when I mentioned that I'd rented a car, that the buses are so much better than driving in the city. Boy was he right! There are designated mass transit lanes on some of the roads and the big vehicles manage to push their way through the traffic jams quite easily. Inside, they are comfortable and clean. Large, softly upholstered reclining seats and air conditioning make watching the featured film pretty enjoyable, and if needed, there is a loo in the back. At one of the stops, a security guard boarded the bus and snapped a photo of each passenger as a record in case there was a theft. Evidently, this had been a problem some time ago but the added precautions have helped. We were also patted down before getting on our bus at both ends.

Once in the city, we took the metro across town to the borough Coyoacan. Despite the train getting very crowded, I was impressed by the fact that it actually smelled good in the subway and in the car. Not like our big apple stations. A man was selling CDs of a Mexican version of Elvis, blaring samples from a set of speakers in a back pack. At one stop, a blind beggar boarded and squeezed through the people in the aisle, singing earnestly for change. The metro system was clean, fast, and efficient.

Once in the city, we took the metro across town to the borough Coyoacan. Despite the train getting very crowded, I was impressed by the fact that it actually smelled good in the subway and in the car. Not like our big apple stations. A man was selling CDs of a Mexican version of Elvis, blaring samples from a set of speakers in a back pack. At one stop, a blind beggar boarded and squeezed through the people in the aisle, singing earnestly for change. The metro system was clean, fast, and efficient.Ours was around the tenth stop so we were well barricaded in against the far wall when we needed to exit but everyone was accommodating when we arrived. Just a few short blocks and we were at the beautiful blue home. Within these tall walls, Frida Kahlo had been born, spent her childhood, and eventually returned to live with her husband, and died. The door was patrolled by a policeman armed with a machine gun, but the neighborhood looked very nice. I was a little crushed to be told there was no photography permitted inside the building. For the sake of sharing with you what we saw, I have borrowed some images.

The brilliant white room that we entered was once the formal living room, a place where the Riveras entertained their international and eclectic set of friends, including Sergei Eisenstein, Nelson Rockefeller, George Gershwin, Leon Trotsky, and caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias, but was now empty of furniture and used as a gallery. There was a massive stone fireplace at one end, near the entry, designed by her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, inspired by the Pre-Columbian art they both loved. The exposed beam ceiling was quite high, also bright white, and the floor was concrete, I suppose, but painted a glossy, blazing yellow, which I've read was to repel insects. It was love at first site, for me, but Joshua didn't think it would work in a home in our climate. I was impressed that he made the distinction. There really weren't many paintings. I guess they've been long since displayed around the world.

|

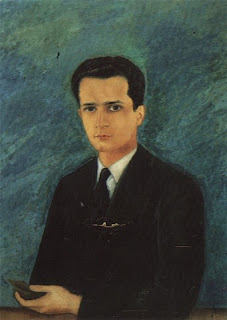

The portrait of Augustin Olmeda 1927was the first painting we saw inside the door, from early in her career as an artist.

By contrast, the portrait of a girl from 1929 had a more immediate and sincere style and captured a more Mexican representation of an indigenous girl. This is the difference to me between a good painting, and not just achieving a technical, uninspired likeness.

The portrait of Wilhelm Kahlo, her father, was completed 10 years after his death but captured his image as a young man. They had been very close and she included an inscription alluding to his honor in the face of epilepsy and fighting against Hitler. He was a professional photographer and her limited palette may have been to assimilate the sepia photos of the day.

The portrait of Wilhelm Kahlo, her father, was completed 10 years after his death but captured his image as a young man. They had been very close and she included an inscription alluding to his honor in the face of epilepsy and fighting against Hitler. He was a professional photographer and her limited palette may have been to assimilate the sepia photos of the day.This still life had been commissioned by the then President's wife to hang in the dinig room of the Presidential Palace, but when it was delivered she refused the painting because of it's overtly sexual symbolism.

The family tree in the second room was never finished. I portrays her granparents at the top and her parents in the center. Along the bottom are herself and her sisters. It is only speculated as to who the figures represent on the lower right - perhaps her sister Christine's two children, or maybe her brother who passed near his birth, or even her never born child.

The family tree in the second room was never finished. I portrays her granparents at the top and her parents in the center. Along the bottom are herself and her sisters. It is only speculated as to who the figures represent on the lower right - perhaps her sister Christine's two children, or maybe her brother who passed near his birth, or even her never born child.The symbolic self-portrait incorporates many symbols relating to her belief that political devotion would deliver her, and everyone, from pain. In the picture, she has disposed of her crutches and is supported by the hand of Marxism, watched over by a wise and knowing eye.

I've always felt that, as a painter, it is a particular treat to see the largely unfinished works of an artist to glean the insight provided into their process. I was surprised to see that Frida drew her work on the canvas with charcoal before painting, an approach I avoid to prevent dirtying my colors. Even at this stage, we found this rather captivating.

This little painting was very unusual and made me a little sad. Created near the end of her life in 1954, the brush strokes and colors are heavy and belabored, without their previous finesse, due to the injections of Demerol and Morphine she required. Her doctor and friend had taken her out for a drive and suggested that she make a sketch. She declined, claiming that she had memorized the scene and created the painting afterward.

The still life with watermelons has often been portrayed as Frida's last work of art but the obvious difference between the brushwork and level detail from those of later painting had left some to believe that the majority of the piece was completed a couple of years earlier and just the inscription and date were added in 1954, just eight days before she died at the young age of 47.

I was particularly taken with this charcoal self portrait but haven't found any photos of it apart from this one that someone managed to snap through museum goers. Also on display were a diary, some sketches, and many letters and photographs. However minor the works may be considered, I studied and appreciated the time with as many as I could, trying to remain considerate of Joshua and Gerardo. I could've quite easily have spent days among these things.

I was particularly taken with this charcoal self portrait but haven't found any photos of it apart from this one that someone managed to snap through museum goers. Also on display were a diary, some sketches, and many letters and photographs. However minor the works may be considered, I studied and appreciated the time with as many as I could, trying to remain considerate of Joshua and Gerardo. I could've quite easily have spent days among these things.The museum presented paintings by Rivera, Paul Klee, Jose Maria Velasco and the couple's friends Marcel Duchamp and Yves Tanguy, too, but I was focused on Frida's work.

It has been recalled that she spent much time in the kitchen when able. On the walls, tiny clay mugs hung to spell out Frida and Diego in the opposite corners, and made the shapes of a pair of doves holding a sash over the window. The tiled counters and wooden shelves were classic Mexican style and a collection of terra cotta pots, masks and figures were displayed.

It has been recalled that she spent much time in the kitchen when able. On the walls, tiny clay mugs hung to spell out Frida and Diego in the opposite corners, and made the shapes of a pair of doves holding a sash over the window. The tiled counters and wooden shelves were classic Mexican style and a collection of terra cotta pots, masks and figures were displayed.The dining room held more folk art including pottery and paper mâché figures. The Burning of the Judases takes place each year on Sabado de Gloria, the Saturday before Easter, during which paper mâché effigies, like the one that hung in the corner, and in other rooms, are stuffed with fireworks and exploded in a great roar of celebration. Quite often, the figures refer not only to Judas' betrayal of Christ in the Bible, but also protest current political decisions, which have led to the festival being banned by those in power at various points in the country’s history. It is easy to see why Frida and Diego collected such figures.

Luncheon guests would sometimes find themselves in the company of the family pets - Fulang Chang, a beloved spider monkey, or Bonito the parrot, who'd perform tricks at the table for rewards of pats of butter. Conveniently for the 300-lb. Rivera, who possessed a gargantuan appetite, the master bedroom was located off the dining room. During our visit, the table had been draped with a multi-colored, embroidered cloth and exhibited one of several colorfully painted wooden toy pick up trucks filled with tiny paper flowers.

|

Nestled in the center of the house and dropped down into the floor a few steps was a nice little reading nook that must stay cool and comfortable all year. This deep, woven davenport nearly filled the small space.

Upstairs, Diego had built an addition for Frida that housed a studio, library, and bedroom. The sun drenched studio had been left pretty much as it was when Frida died. I don't think the unfinished portrait of Stalin was on the easel, given her by Nelson Rockefeller, and I don't recall the barrier keeping us from close examination of her pigments and tools. Originally, Frida's intention was to become a doctor, but at the age of 18, an awful bus accident left her severely injured and with a deteriorating spine. While bedfast from the accident, her family and friends encouraged her to paint, to fill the time and lift her spirits. Her mother had a mirror affixed to the canopy so she could paint self portraits while lying down. Once able, she pursued the opinion of the renowned artist and political activist Diego Rivera which led to their life long, tumultuous relationship during which they married each other, divorced, and remarried.

Originally, Frida's intention was to become a doctor, but at the age of 18, an awful bus accident left her severely injured and with a deteriorating spine. While bedfast from the accident, her family and friends encouraged her to paint, to fill the time and lift her spirits. Her mother had a mirror affixed to the canopy so she could paint self portraits while lying down. Once able, she pursued the opinion of the renowned artist and political activist Diego Rivera which led to their life long, tumultuous relationship during which they married each other, divorced, and remarried. Apart from continuous emotional distress, the petite woman of such strong character was at constant battle against the result of childhood polio, from which she nearly died in 1925, and the pain of over 30 surgeries, eventually requiring her leg to be amputated. Knowing this, I nearly burst into tears when I came into the room displaying one of her tiny, plaster medical corsets, like the one seen here on her bed. The incessant pain that she suffered for the rest of her life was ever present in her work and in her home.

Lying on the bed was her little brown death mask, surrounded by one of her scarves. On the headboard was a painting of a dead child and at the foot of the bed a photo assemblage of Stalin, Lenin, Marx, Engels and Mao. Stalin became a hero to Kahlo after she and Rivera had a falling out with Trotsky. Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954 in this tiny room overlooking the gorgeous tropical garden. After her wake, she was cremated and her ashes were returned to Casa Azul where they reside now in an urn in the bedroom.

The window on the top floor is the studio, the lower level houses an open air gallery of the Pre-Columbian sculptures like those above.

Another view of the studio, on the upper level to the left, and the far bedroom to the right.

The colonial-style house forms a U-shape around a central courtyard. This cheerful space, populated by Teotihuacan idols and luxuriant tropical plantings, is where Frida romped as a child and, as an adult, worked on her paintings and held art classes. In 1943, Frida became an instructor for the Escuela de Pintura y Escultura de La Esmeralda, but her physical condition required here to mostly give classes at her home. These students eventually number only four and were called “Los fridos”: Fanny Rabel, Guillermo Monroy, Arturo “el Güero” Estrada and Arturo García Bustos, who gathered to work on the patio. By 1945, Frida was once again confined to bed in the house.

Among the photographic signs placed throughout the garden was this picture of the couple, looking lovingly at one another, standing on the balcony outside Frida's bedroom, a glimpse of which you can see through the open doors. There were also quotes on these signs, one of which I found extremely inspirational and encouraging; "Feet, why do I need them when I have wings to fly?" Frida wrote these optimistic words in 1953, near the end of her life, after years of constant pain. Makes me rethink my complaints.

It seemed like the thing Joshua was most excited about in the whole museum was this bird of paradise in full bloom.

One of the most whimsical touches at the Casa Azul is a small pink stepped pyramid Rivera built in the garden displaying more pre-Columbian idols. At Frida's death in 1954, he gave the Casa Azul and its contents to the Mexican people with the stipulation that it not be opened until 4 years after Frida's passing.

Restoration work was performed on the building and some of its contents in 2009 and 2010. The work was sponsored in part by the German government, who donated 60,000 for the effort and the museum itself which contributed one million pesos. The effort concentrates on obtaining furniture for display and preservation, other equipment, roof work, restoration of items in the collection. Earlier, a gift shop and tea room had been added. Most of the souvenirs seemed too similar to the myriad of products out there sporting Frida's likeness but they did have a selection of linoleum cut prints by a local artist of Dia de Los Muertos characters. I bought one of Catrina, the upper class grande dame in the big feathered hat.

In 2004, a trunk was discovered in the back of an old wardrobe that had been forgotten in an unused bathroom. Curators opened the lid to find hundreds of Frida Kahlo's colorful skirts and blouses, many still infused with the late artist's perfume and cigarette smoke. It took two years to log and restore the nearly 300 articles of clothing, which were then displayed as part of the 100th anniversary of Frida's birth.

Hesitantly, and thankfully, I bid Frida and her blue house farewell. Gerardo and Joshua had been immensely patient and we would be traveling a while before we'd be home for the night.

A couple of Coyoacan buildings.

A cab took us to the bus station where we purchased tickets and drinks just in time for our ride. I was delighted to see cans of beer in the refrigerator and asked if we were allowed to drink a beer on the bus. Gerardo thought so and I couldn't resist, just for the novelty, but when we went through the security checkpoint and got patted down the man said I had to leave it on his podium. I was only a little disappointed but just before we departed, the driver came back and explained to Gera that he'd rescued my unopened beer and stowed it in the baggage compartment for me to retrieve when we got to Pachuca. Nice man.

I was utterly amazed by the endless miles of urban sprawl in every direction. It was explained to me that much of the building was illegal having been permitted by upcoming officials to gain votes. Many of the areas don't have public works, like water, so tanker trucks drive in supplies periodically. The contour of the land is virtually obliterated by the jagged, nearly solid covering of millions of tiny, cinder block cubes. No wonder those who can afford to paint their house an intensely vivid color.

Charmingly, this relatively new church sits on the outskirt of town to leave a final positive and hopeful impression.

Once again, the sun went down as we drove toward Pachuca.

I conclude my telling of our trip with our last Mexican sunset and strongly suggest that if you have the opportunity, definitely visit this beautiful country.

No comments:

Post a Comment